The Brain as an Organ of Soul: A Functional Analogy

The brain, while fundamentally a biological organ, also functions as an interface for consciousness—a receiver, integrator, and processor of experience. Recent developments in neuroscience and consciousness studies suggest that its physical architecture parallels many systems found in nature, particularly those that optimize connectivity and flow.

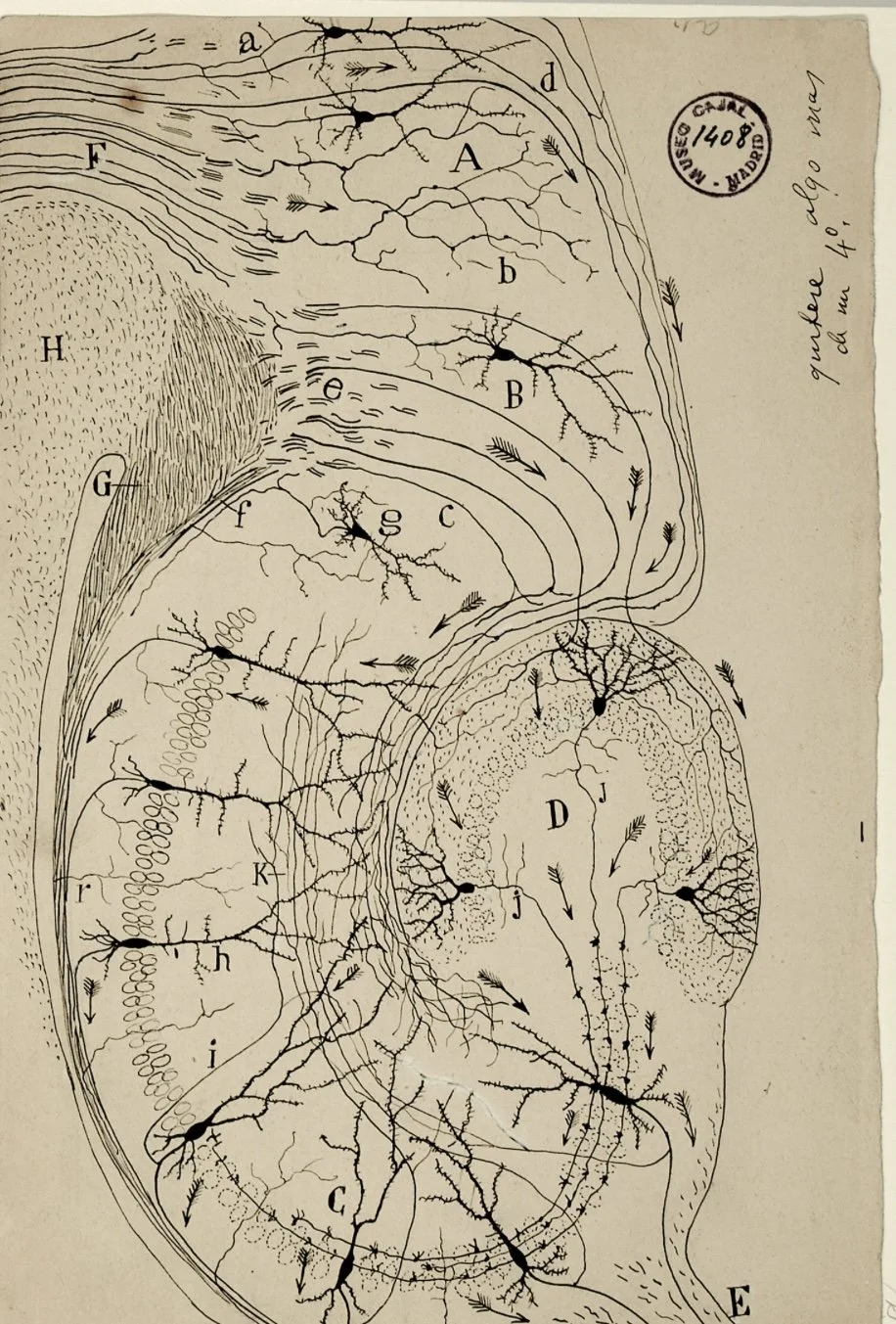

Take the shape and function of synapses: the points where neurons communicate through electrochemical signals. These resemble, both in form and function, the branching patterns of tree roots and mycelial networks. Mycelium, the underground fungal network, distributes information and nutrients across vast distances through a decentralized yet highly efficient architecture. Similarly, the brain’s synaptic network allows for rapid transmission of signals across specialized regions, enabling the dynamic regulation of memory, emotion, and perception.

The default mode network (DMN), often studied in both meditation and psychedelic research, illustrates the brain’s capacity to self-organize and also to temporarily dissolve that organization. Under normal conditions, the DMN is responsible for internal narratives, self-referential thought, and mental time travel (thinking about the past or future). During meditation or under the influence of psychedelics like psilocybin, the DMN becomes less active or more flexible, allowing for a broader integration of sensory and emotional data. A 2014 paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Carhart-Harris et al. demonstrated that under psychedelics, brain regions that normally do not communicate start forming temporary but coherent networks. This pattern closely mirrors the way tree roots will extend toward new sources of water or nutrients in times of scarcity—a temporary shift in structure to accommodate environmental demands. It further signifies, that the suspension of this particular area, draws one directly into the present.

It’s important to understand that psychedelics, while powerful, are not in themselves the source of consciousness or even of transformation. The energetic flow that occurs during these altered states is not produced solely by the substance, but rather by the meeting point between the psychedelic and the consciousness of the individual. An Alchemical dialogue. This is where the real shift happens: where the compound interacts with the existing architecture of the mind, the nervous system, and the unique awareness of the user. Many people can take psychedelics and remain energetically blocked, trapped in loops of thought or emotion, because the substance alone does not liberate. It is the openness, the readiness, the state of internal receptivity that determines what kind of state unfolds. In this way, the psychedelic is neutral—a catalyst, not a conductor. It provides energy, perhaps even introduces the intelligence or spirit of a plant, but it does not direct. The user is the one who shapes the experience. The mind—especially when aware of itself—becomes the conductor of the energy the psychedelic provides. This relationship is not passive; it is a dialogue. And in this dialogue, the potential for further consciousness arises not from the compound, but from the quality of the meeting. Within a broader context of life, one can also see the use of psychedelics as a teacher of the many forms. It can provide a particular perspective, it can be a teacher, a helper, but it is not the whole picture. There are many ways to access the realm beyond the mind, this is one of them, but more inclusively it is life itself that brings one to the precipice of the beyond, whether or not plant substances are involved.

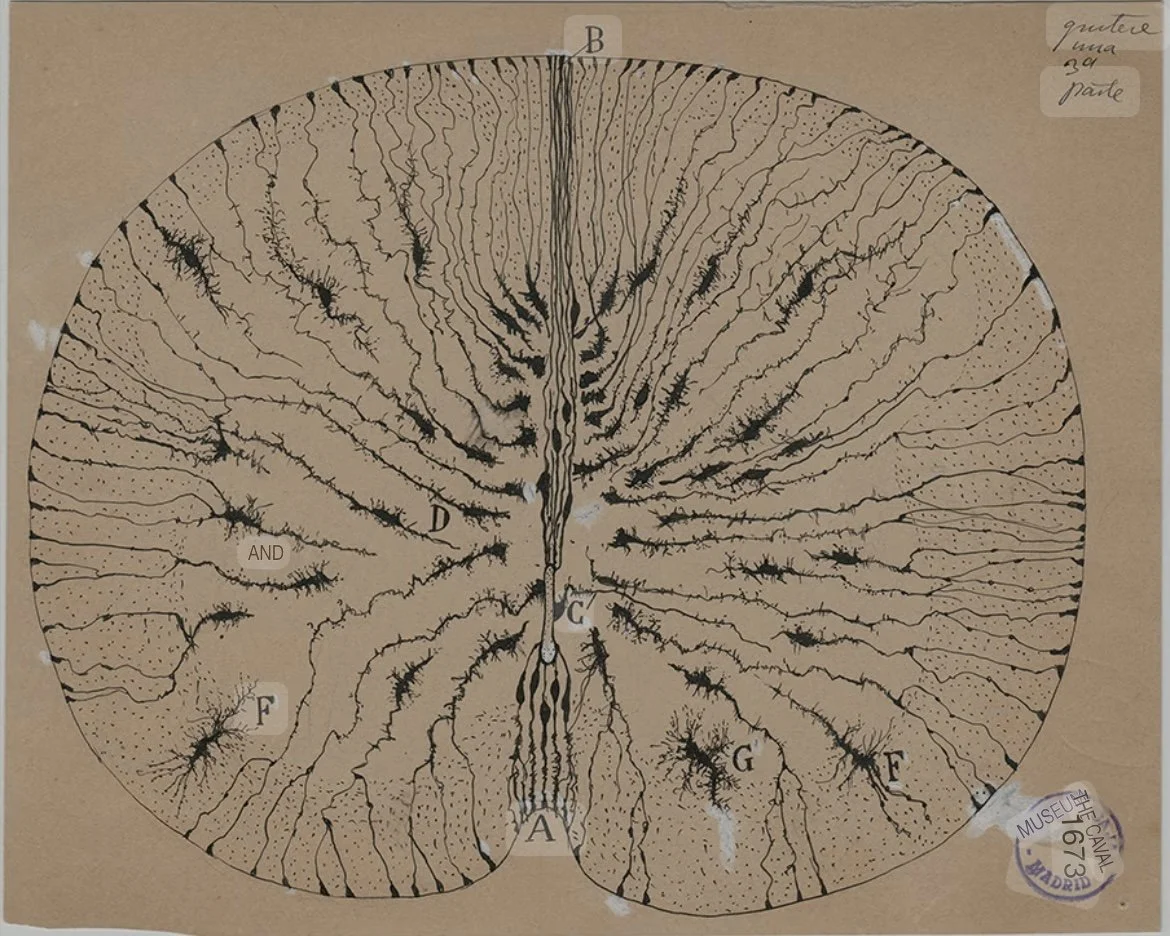

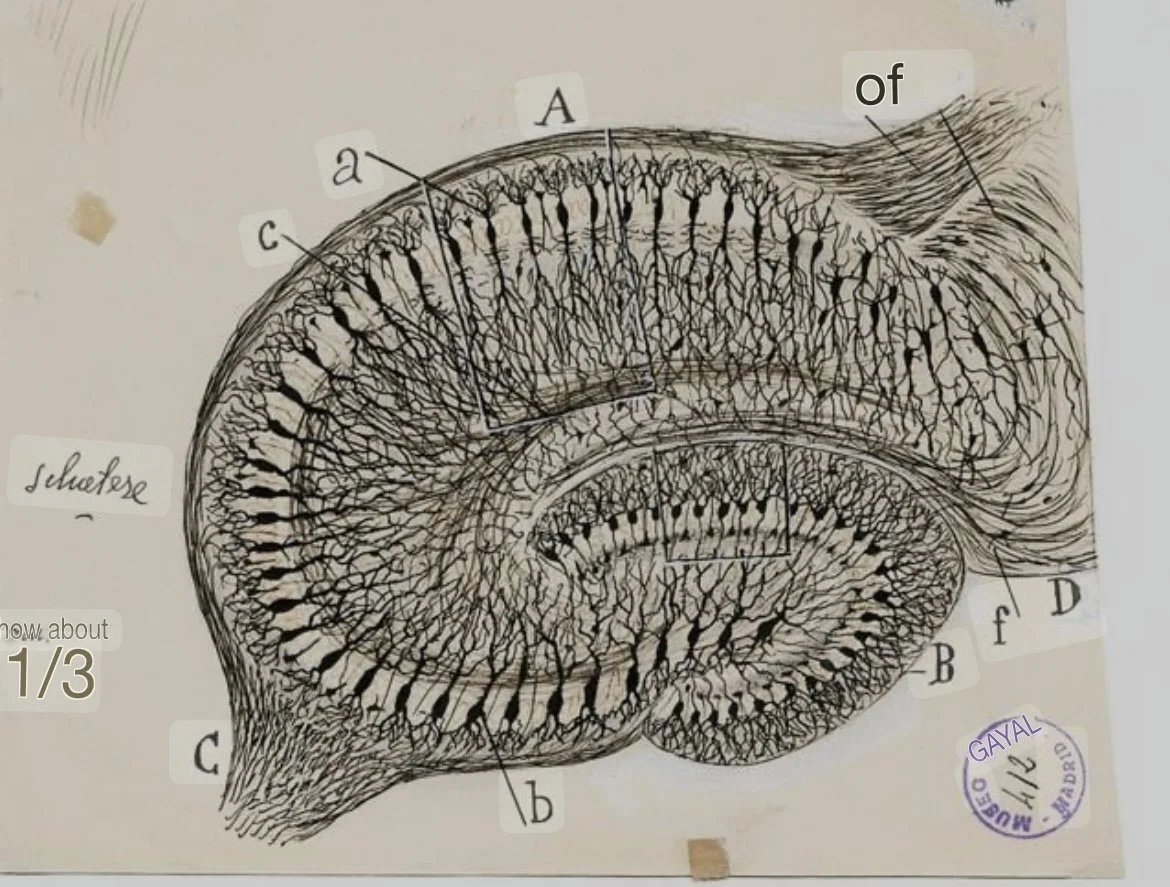

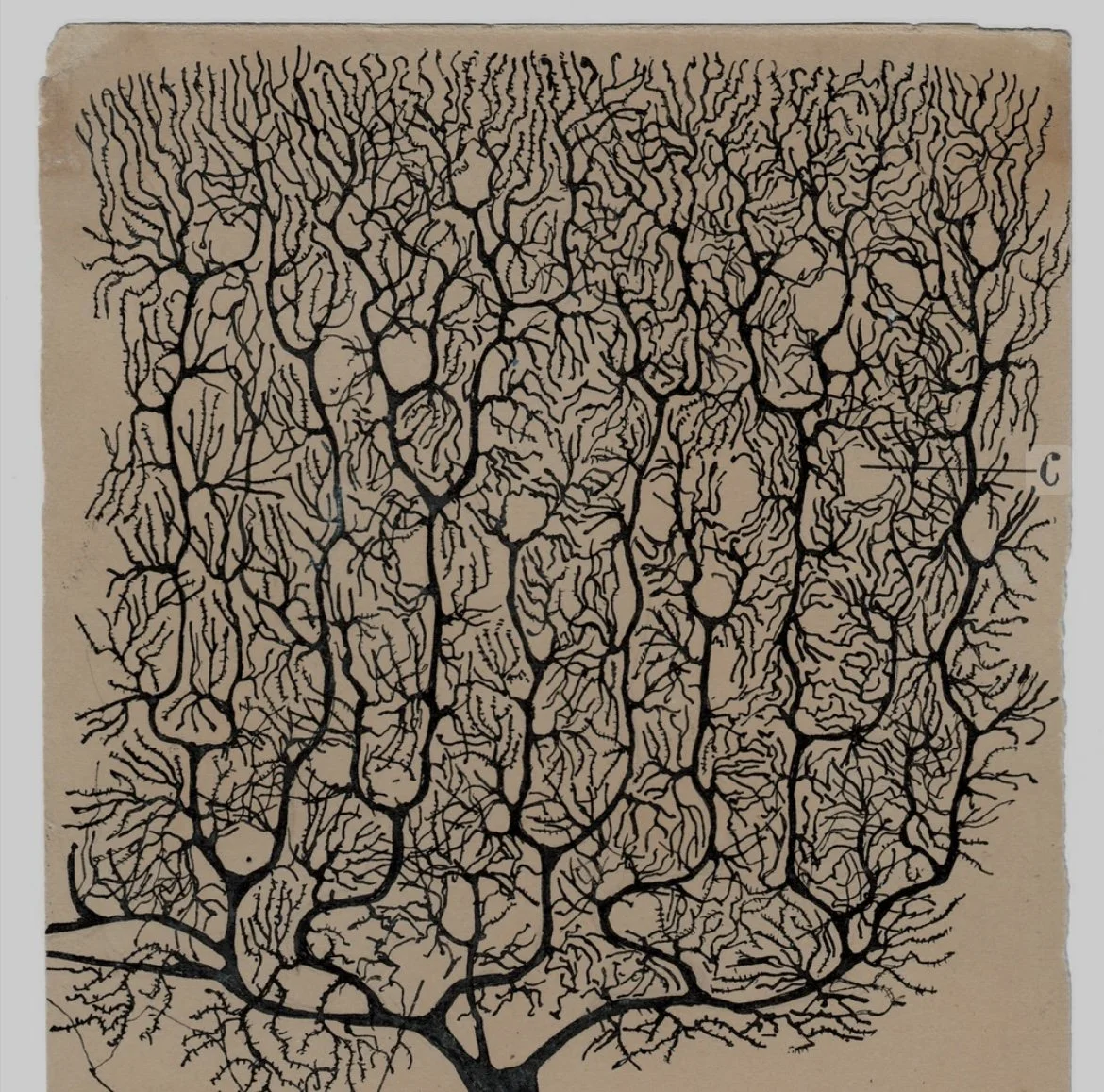

There is also a striking similarity between the way dendritic trees (the branching structures of neurons) form and the way lightning forks, rivers branch, or leaves vein. All follow principles of energy minimization and surface area maximization. This shared logic suggests that the brain’s shape is not arbitrary—it follows the same physical rules that govern fluid flow, electrical conduction, and nutrient distribution in nature.

If we define the “soul” functionally—not as a fixed metaphysical entity, but as the total expression of self-awareness, memory, sensitivity, and imagination—then the brain becomes its primary organ. This does not negate spiritual interpretations; rather, it roots them in observable phenomena. States of spiritual insight, experienced in deep meditation or facilitated by psychedelics, show reduced ego activity, heightened sensory integration, and a dissolution of typical boundaries of self—all of which have been documented through fMRI imaging and EEG coherence studies.

Ultimately, the brain’s complex organization mirrors the web-like logic of ecosystems. Like a forest, the brain relies on modular sub-systems (such as the limbic system, the prefrontal cortex, the brainstem) that specialize in unique functions but remain interdependent. Just as an ecosystem collapses if one species disappears, the brain cannot function if even a small neural network is compromised. The parallel isn’t symbolic—it’s structural.

The brain is an organ of soul not because it holds spirit metaphorically, but because it is the most complex, dynamic, and integrative system through which consciousness emerges—interfacing biology with awareness, the material with the immaterial.

Monkey puzzle, May 2025

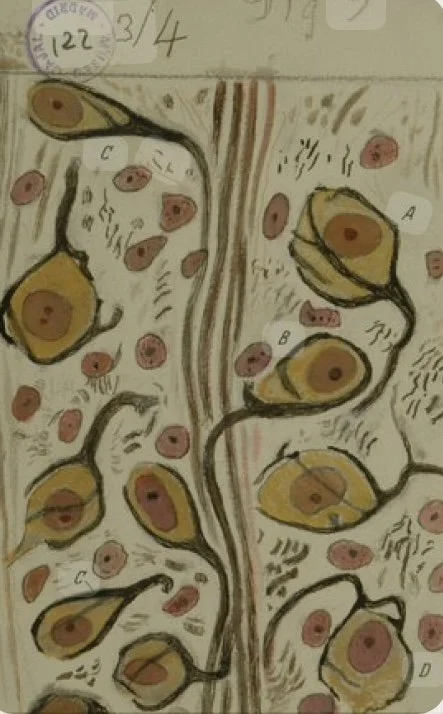

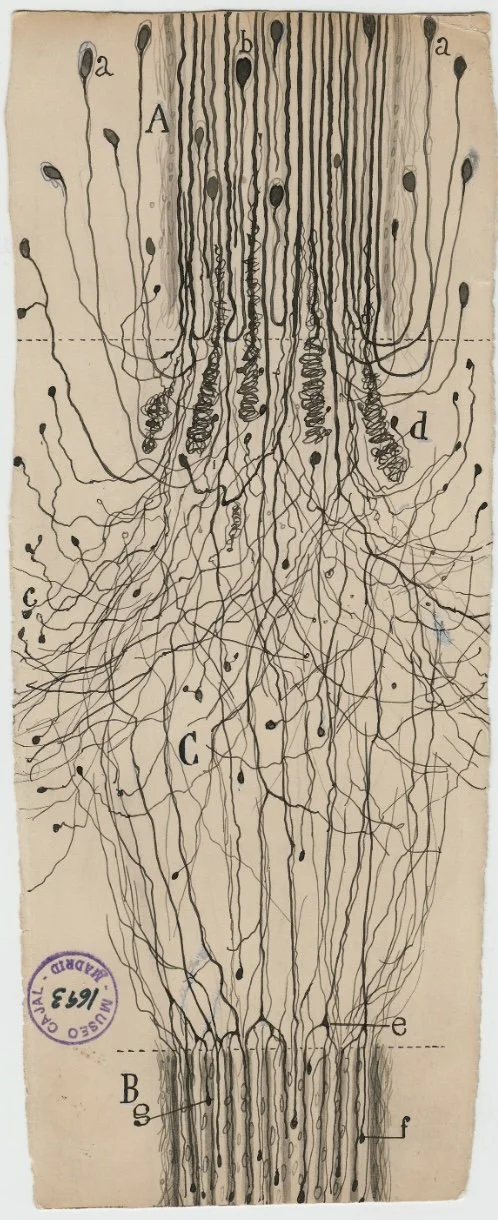

Images from the series — The beautiful brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramon y Cajal

A purkinje neuron from the human cerebellum 1899, ink and pencil on paper.

Santiago Ramon y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934) was a pioneering Spanish neuroscientist and histologist, often regarded as the father of modern neuroscience. In an era when the brain was still largely a mystery, Cajal transformed the field with his detailed observations and artistic renderings of neural structures, using the Golgi staining method to reveal the intricate architecture of the brain. He was the first to conclusively demonstrate that the nervous system is made up of discrete cells—neurons—rather than a continuous network, a theory that became known as the neuron doctrine.

Cajal was also a philosopher of the mind. In his collected works, such as “Histology of the Nervous System” and “Advice for a Young Investigator”, he reflected deeply on the brain not just as a biological machine, but as a creative and evolving system. His drawings of pyramidal neurons, Purkinje cells, and other brain structures are still used today, not only for their accuracy but for their poetic vision—capturing the brain as a forest of communicating trees. Cajal believed that understanding the brain’s structure was the first step toward understanding consciousness itself. His work laid the foundation for modern studies of neuroplasticity, perception, and the physiological basis of thought and imagination.

One series he calls ‘the beautiful brain’, a symbolic reflection of the intricate and creative structures that lay within human anatomical systems.